Dull and stupefying dread re-arrived in waves all of 2019. A lot of it was around Big things: specifically, young climate activists emerged to once again reiterate our situation and behavior in new starkness. Bloating social media avenues delivering continuous Big news—information supposedly empowering and connecting—ironically make me feel powerless and unmoored.

I wanted to instead illustrate something simple, factual, and contextually precise, that might tell a story with only a shape. Here's last year’s daily temperatures, specific to my local region, stacked up again the expectation and experience of the previous generation.

This is not a proper data visualization, but maybe rather a data-based illustration. For example, the chart is absurdly, unpublishably wide, trying to keep each of the 365 days fairly square. I don’t even expect anyone to scroll all the way, really looking. But it’s there if you choose to. It’s more suitable for a long wall decal, or a necklace:

But it’s still visualizing data. (Stefanie Posavec, one of my favorite information designers, rather calls herself “a designer, artist and author whose favoured creative material is data.”) This chart’s purpose is not chiefly informative or communicative but documentary and decorative. I think that’s fine. Plenty of weather data charts exist that scientifically depict the extremes we live in. What about a minimal and hyperlocal approach instead?

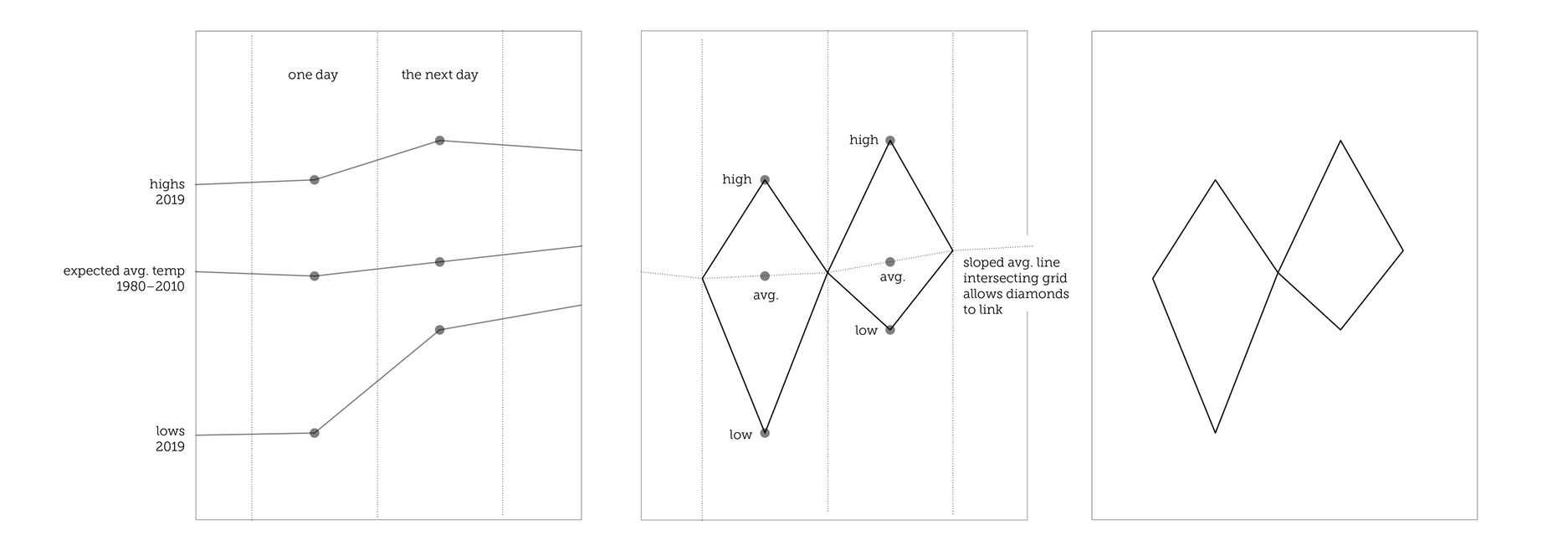

Rather, the shape led here: I was doodling with shapes and patterns when I linked together some fat and tall diamonds and thought: could the dimensions be taken from something, represent numbers?

The vertical points of the diamond diminishing from a fat middle suggested peaks, diminishing from a dense average—similar to a simplified box-and-whisker plot. Climate data was the first appropriate example I thought of, and this chart is some proof-of-concept for the diamond.

That being said, I do think the diamond shape has informative effects: the outlier points stretch out the diamond, feeling pointy in relation to how extreme the peaks are. The chain of diamonds look best when the centers kiss—best for slowly sloping averages. When the points don’t straddle the average but rather both fall above or below it, the diamond transforms strikingly into an arrow, informatively pointing in the direction of the deviation.

Or I don’t know. This is the test.

The diamond chart really just stitches together three line charts. Each day-diamond relates past to present—it relates a generation of aggregate expectation (temperature “normal”) to a new single day. The tension of this relationship gives the chart its feel. It’s a distinct profile for this single year, in my single city.

This was my first time, in my own work, illustrating data I didn’t personally collect. It was also my first time using Adobe Illustrator’s graph tool in my own work. Obviously, turning 1000+ points into vector line graphs went much faster this way. However, I stitched the diamonds together, as shown above, manually, point to point with the pen tool. It was a time suck, but done in the first days of the new decade, it made me feel the day-by-day nature of a year, touching each individual high and low, which varied widely as the months rolled by, their averages arcing up and down almost imperceptibly.

Gathering personal data manually before, I appreciate keeping (only) one tedious, manual aspect to keep me in touch with data that is both big and small, old and new, global and local.

[2019 highs and lows taken from usclimatedata.com and wunderground.com. 1981-2010 daily averages from NOAA at w2.weather.gov]